McMenamins Kennedy School History Pub, June 24, 2019

50 Years After Stonewall:

Looking back on how it has impacted Portland's LGBTQ community

A shorter version of this piece was delivered by Jeff Stookey for McMenamins Kennedy History Pub, Portland, OR, on June 24, 2019, in commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of the Stonewall Riots. He accompanied a panel that included, Walter Cole/Darcelle, Holly Hart, Susie Shepherd, and Kathleen Saadat.

- More about Holly Hart

- More about Susie Shepherd

- More about Walter Cole/Darcelle

- More about Kathleen Saadat

Follow this link to a video of the event on the Oregonian's Facebook page.

I want to thank the Kennedy School’s History Pub for reaching out to the Gay & Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest (GLAPN for short) to put together this program. GLAPN partners with the Oregon Historical Society, which is also a partner with the History Pub. And thanks to the panelists for participating.

I want to thank the Kennedy School’s History Pub for reaching out to the Gay & Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest (GLAPN for short) to put together this program. GLAPN partners with the Oregon Historical Society, which is also a partner with the History Pub. And thanks to the panelists for participating.

I’m here this evening to set the context for the Stonewall Riots and the movement for LGBTQ rights that followed, particularly here in Oregon.

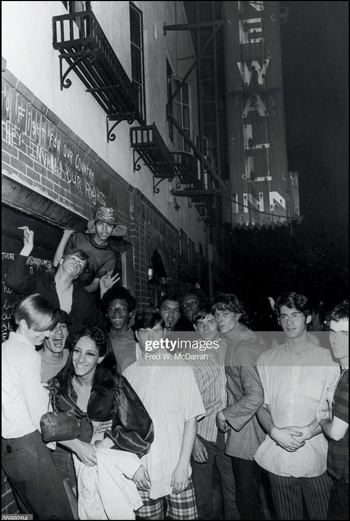

Over the weekend of June 27, 1969, the Stonewall Inn bar and surrounding area of New York City were the site of a series of demonstrations and riots that rose up in response to a police raid on that gay establishment.

I didn’t hear about the Stonewall riots until years after it happened. But my partner, who was in the military at that time, was subscribing to the Village Voice as his link to the gay world, so he learned of those events soon after they occurred.

I have written a historical novel trilogy, Medicine for the Blues—a gay love story set in 1923 Portland. This work took me on a deep dive into gay history which I could not have done without help and guidance from GLAPN.

I have written a historical novel trilogy, Medicine for the Blues—a gay love story set in 1923 Portland. This work took me on a deep dive into gay history which I could not have done without help and guidance from GLAPN.

They have a terrific website which I encourage you to check out. Indeed much of my talk tonight is information from that website.

Robin Will, president of GLAPN, wrote of Acquaintance, book one of my trilogy:

“Fiction makes the reality of the 1920s far more vivid than a historical text ever could. Eugenicists in Oregon were calling for sterilization of perverts along with other undesirables, and the Ku Klux Klan had infiltrated every level of the community, secretly ready to strike against anything that didn’t seem 100% normal and American. It wasn’t an auspicious time for two young Portland men to fall in love with each other.”

Let me put in a plug here for the Holy Names Heritage Center, which also partners with the History Pub. I first learned about the Ku Klux Klan history from an article about the 1922 Oregon School Law written by my friend Michael Nove who did much of his research at the Holy Names archive. The law was a successful ballot initiative that made it compulsory for all children between age 8 and 16 to enroll in public schools, with the intent of strangling Catholic school enrollment—Catholicism being a primary target of the KKK at the time—much the same as Islam is a political target today. The US Supreme court overturned this Oregon state law with the 1924 decision in Pierce v Society of Sisters.

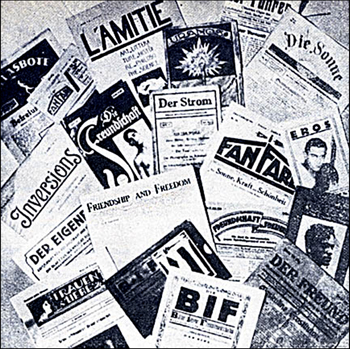

Now, Stonewall was not the first fight against oppression of homosexuals. As early as the 1870s, gay people in Germany were working to decriminalize homosexual acts—a movement that flourished after WWI.

Now, Stonewall was not the first fight against oppression of homosexuals. As early as the 1870s, gay people in Germany were working to decriminalize homosexual acts—a movement that flourished after WWI.

The main character in my novel is a young doctor who served in the US military in WWI and after the armistice he spent time in the allied occupation of Germany. There he learned of this early homophile movement.

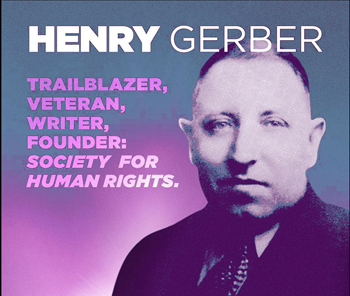

Elements of this scenario are based on the life of Henry Gerber who served with the US army of occupation from 1920 to 23 and became familiar with the German homosexual emancipation movement.

Gerber was in contact with Magnus Hirschfeld’s Scientific-Humanitarian Community in Berlin where Hirschfield established the first sexology institute in the world with an immense library. You can guess where that ended—the Nazis burned the library in the streets in 1933.

Gerber was in contact with Magnus Hirschfeld’s Scientific-Humanitarian Community in Berlin where Hirschfield established the first sexology institute in the world with an immense library. You can guess where that ended—the Nazis burned the library in the streets in 1933.

When Henry Gerber returned to Chicago in 1924, he and a few friends started a gay rights organization, the Society for Human Rights, incorporated in the state of Illinois, and published a newsletter, "Friendship and Freedom.” Following a police raid of Gerber’s home, he lost his job at the Post Office and spent his life savings defending against his prosecution for “deviancy.”

When Henry Gerber returned to Chicago in 1924, he and a few friends started a gay rights organization, the Society for Human Rights, incorporated in the state of Illinois, and published a newsletter, "Friendship and Freedom.” Following a police raid of Gerber’s home, he lost his job at the Post Office and spent his life savings defending against his prosecution for “deviancy.”

Here in Oregon sodomy laws were on the books from 1853 until 1971. In 1912 the Vice Clique Scandal broke, involving some 68 Portland men, including a number of professionals. Although a few were convicted of sodomy, most never went to trial. Some left town and some had the charges against them dismissed.

As a result of this scandal, which appeared in local papers, the legislature expanded the sodomy laws to include almost any sexual behavior what was not the heterosexual missionary position.

Also in 1913, a eugenics law was passed to permit the sexual sterilization of a number of people, including “sexual perverts” and “moral degenerates.” This law was repealed the same year by a citizen ballot initiative.

In effect, this could be seen as the nation’s first Gay rights referendum.

Then in 1923 yet another sterilization law passed and remained on the Oregon book until 1983. During that time more than 2500 people in Oregon state prisons and mental hospitals were coerced into sterilization.

In 2002 Oregon Governor John Kitzhaber issued a formal apology to those who had been sterilized.

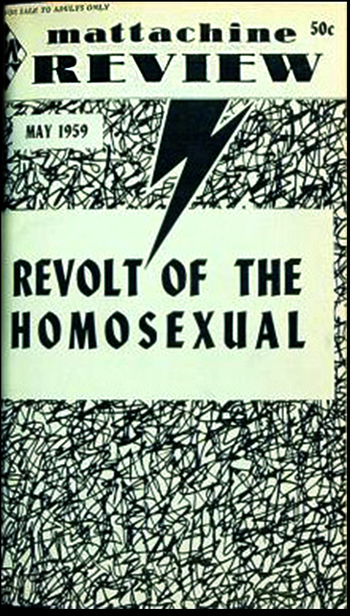

Moving forward to 1948, Harry Hay put out the call for a gay movement in Los Angeles, then he formed the Mattachine Society in 1950 and began organizing gay discussion groups.

Moving forward to 1948, Harry Hay put out the call for a gay movement in Los Angeles, then he formed the Mattachine Society in 1950 and began organizing gay discussion groups.

By 1953 there were more than 2000 members in California. When Harry Hay’s Marxist background was exposed that year, he stepped down from the Society to protect it from McCarthyism.

Still Harry Hay continued to advocate for gay rights and when the Stonewall riots occurred in 1969, he declared that the East Coast was finally catching up with California.

US Senator Joseph McCarthy went after alleged Communists in the federal government from 1950 until his censure by the Senate in December 1954, using the term “security risk” as a euphemism to include homosexuals. However, these “security risk” purges predated McCarthy, going back to 1947, and became institutionalized within the federal system, becoming standard government policy until the 1970s.

In 1955 a lesbian organization named the Daughters of Bilitis was formed by Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin in San Francisco.

By 1959 there were chapters in New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Rhode Island.

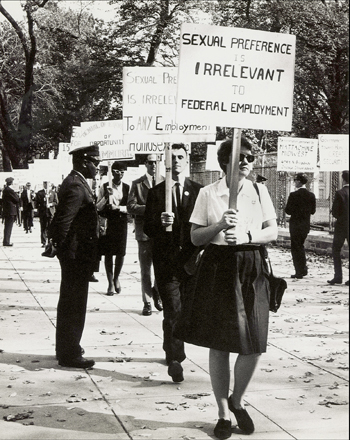

During 1965 an umbrella group including the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis staged a number of picket lines in front of the White House in Washington, DC, and Independence Hall in Philadelphia, protesting the treatment of homosexuals.

During 1965 an umbrella group including the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis staged a number of picket lines in front of the White House in Washington, DC, and Independence Hall in Philadelphia, protesting the treatment of homosexuals.

During these years “sexual deviance,” same-gender dancing, and cross-dressing were illegal and police raided gay bars across the country.

But World War II fostered a new social life as young people with same-sex longings left home to join the military and had the chance to explore their sexuality. An atmosphere of relative lax morality and social dislocation provided opportunities in Portland and Seattle for lesbians and gay men. An increasing number of bars began to cater to these customers.

In 1950, Portland Mayor Dorothy McCullough Lee attempted to close down some of the gay and lesbian bars that had been thriving in the city since the 1940s. She only succeeded in closing down drag shows in one bar, while numerous other gay and lesbian bars continued for varying periods of time during the 1950s and 60s.

After Mayor Lee’s crackdown, Portland law enforcement officials seem not to have raided local gay bars. Mainly Portland police exercised a hands-off policy, believing it was better, in their words, “to have deviates concentrated in a few places.” In addition to this informal policy, Mayor Lee’s vice and graft crusades in the early 1950s ended the system whereby illegal and questionable entertainment establishments paid police to leave them alone. As a result, Portland’s few bars and their patrons were not mired in quite the desperate situation as were those in New York City, San Francisco, or even Seattle.

A collision between the shifting culture and Portland’s conservative establishment occurred in the heat of the divisive 1964 presidential campaign between Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwater. Mayor Terry Schrunk and the Portland city council launched the first concerted attack against gay and lesbian bars since Mayor Lee’s campaign in 1950. After a series of hearings in late 1964, the city moved to shut down six bars, pressuring the Oregon Liquor Control Commission to revoke their licenses.

The bars hired attorneys who argued that shutting the bars because of the type of customers they catered to violated the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which protected people who assembled in public accommodations. When the OLCC agreed, there was little else the City could do.

Then in 1969 came the Stonewall Riots, and growing activism began in Portland’s LGBTQ community, leading to a number of firsts for Oregon over the decades that followed.

Then in 1969 came the Stonewall Riots, and growing activism began in Portland’s LGBTQ community, leading to a number of firsts for Oregon over the decades that followed.

Some examples:

1971 - After being fired from her Oregon teaching job, Peggy Burton was the first LGBTQ public school teacher in the U.S. to file a federal civil rights suit, and the first one to win.

1972 - The Democratic Party of Oregon was arguably the first state major party platform in the nation that adopted a sexual orientation civil rights plank.

1973 - Oregon House Bill 2930 would have banned sexual orientation discrimination in employment and housing but lost by two votes and never went to the Senate. It was likely the first such bill in the country.

In the 1980s Audria M. Edwards became the first African American president of any PFLAG chapter in the nation.

1985 - Oregon attorney Cindy Cumfer handled the first same-gender parent adoption in the United States. It served as a prototype for adoptions around the country.

1998 - Tanner v. OHSU. The Oregon Court of Appeals became the first court in the nation to decide that government is constitutionally required to recognize domestic partnerships for purposes of employee benefits at government entities.

2003 - Rives Kistler was the first openly gay male state supreme court justice in the nation.

2006 - Virginia Linder was the first openly lesbian state supreme court justice.

Earlier Kistler and Linder wrote an amicus brief in opposition to Colorado’s anti-gay Amendment 2 adopted in a 1992 statewide referendum, the same year that Oregon’s anti-gay Measure 9 was defeated. The case was appealed to the US Supreme Court. The reasoning applied in the Oregon amicus brief was used in the majority opinion issued by Justice Anthony Kennedy, which declared Colorado’s law unconstitutional. Kennedy later extended the reasoning from that decision to subsequent cases and similarly invalidated laws banning homosexual conduct, the Defense of Marriage Act, and prohibitions against same-gender marriage.

2008 - Portland was the first of the nation’s 40 largest cities to elect an openly LGBTQ mayor, Sam Adams.

2009 - African American mother Antoinette Edwards founded PFLAG Portland Black Chapter, the first PFLAG group in the country created by and for the Black community.

2013 - State Representative Tina Kotek was the first openly lesbian woman to head a state legislative chamber when she became Oregon House Speaker.

2016 - Oregon was the first state to elect an openly LGBTQ governor, Kate Brown, who had long identified as bisexual.

We Oregonians have a right to be out and proud.

P.O. Box 3646 • Portland, OR 97208-3646 • info@glapn.org

Copyright © 2018, Gay & Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest