Egypt’s Fearful Gays Shy from HIV Testing

Pittsburgh

Post-Gazette, March 14, 2005

By Anita Srikameswaran

|

Associated

Press

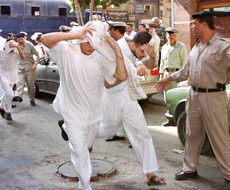

Some of the 52 men arrested at an alleged gay gathering at a Nile River

boat restaurant cover their faces as they enter a state security court

for trial in July of 2001 in Cairo where they faced a range of charges

rooted in the nation’s obscentiy and public morality laws. This widely

publicized raid and subsequent prosecutions heightened gay distrust of

the government and is complicating current measures to combat the spread

of HIV. |

CAIRO, EGYPT—In May 2001, police

raided the Queen Boat, a floating nightclub moored on the Nile River, and

arrested 52 gay men.

Ultimately, judges sentenced one defendant to five years

in prison for debauchery and deriding religion, another to three years for

deriding Islam, and gave 21 others three-year prison terms to be followed by

three years of probation for “habitual debauchery.”

Human rights groups around the world protested that the

arrested men had been beaten and threatened with torture to confess their

“crimes.”

The Queen Boat incident began what many see as a

crackdown on homosexuality, heightening gay people’s distrust of the

government and driving them even further into hiding.

So now that the government is offering anonymous HIV

testing for the first time, many gays are understandably wary.

Some suspect that if they get tested for the infection,

they could be identified publicly as gay, which could lead to imprisonment

regardless of their HIV status.

“It’s not anonymous [testing], don’t believe

that,” warned one gay Egyptian who asked not to be named. “The first thing

they do is call the cops.”

The 22-year-old man said that when his partner visits the

United States, friends ask him to bring back HIV tests that can be done at

home, so that they can learn their status in private.

However, the only home-based test that is approved by the

U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires that the blood sample be mailed to

an American lab. Other home test kits have an indicator window and promise

results in 15 minutes, much like a pregnancy test, but the FDA doesn’t

consider them reliable.

Do Infected Gays Disappear?

Rumors of HIV-positive gay men disappearing add to the

fear.

The Egyptian gay man spoke of trying to track down an

infected acquaintance to offer help. He couldn’t find the man and his family

had no information on his whereabouts.

“Either they disappear or they stop having sex with

people because they are too scared or they leave the country to get

treated,” he said. Besides, “it’s becoming very, very difficult for any

AIDS patient or HIV-positive patient to go and seek medication [in Egypt].

There have been too many horror stories lurking around.”

Dr. Khalil Ghanem, of Johns Hopkins University, said

HIV-positive people in Saudi Arabia and Lebanon, both gay and straight, have

similar concerns about being stigmatized.

Those “who have money are actually leaving the country

and getting treatment somewhere else,” he said. “They go to France, they

go to Switzerland, to the United States for care.”

Ghanem pointed out that people who leave don’t get

counted in official case numbers. A small number of others, he said, may

strongly suspect that they are infected, but avoid being tested.

“They are essentially dying without care,” he said.

In Egypt, the same conservative social norms that make

gays so fearful also make it hard to preach HIV prevention methods.

In this predominantly Muslim culture, both homosexuality

and sex outside marriage are considered sinful, so any discussion of safe sex

among unmarried partners or gays could amount to condoning forbidden behavior.

“Premarital and extramarital sex are not accepted

socially and culturally,” said Dr. Nasr El-Sayed, leader of the AIDS program

for Egypt’s Ministry of Health. “The girls should be virgins. It’s not

accepted for the girl to not be a virgin when she gets married.”

As in other countries, people are not as young as they

used to be when they wed. The marriage contract specifies that the prospective

groom must provide the bride with a suitable apartment, but even down payments

are far out of reach for the average worker.

So some men in the Middle East, unwilling to wait for

years before they can have sanctioned sex with their wives, have sex with

other men—but they don’t consider themselves homosexual or bisexual.

Bob Preston, an American gay man who does consulting work

in Egypt, said these Egyptians “don’t have access to have sex with women,

so they have sex with men and it’s OK because they’re not married yet.

They don’t think of it as gay sex [if] they’re the active partner,”

meaning they take the male role during intercourse.

A Bisexual Pattern

One of Preston’s friends even attended the wedding of

his Egyptian male partner of several years, and Preston broke off a

relationship because he didn’t want to play out the same scenario.

“He showed me the apartment he bought for his

wedding,” Preston recalled. “He was having it remodeled. And we went out

with his straight friends.”

Female prostitutes do exist as another outlet for

unmarried men, but they are believed to have longer relationships with fewer

partners.

The hidden world of gay sex and the obscurity of

prostitution worry those who want to test for HIV.

“In Middle Eastern countries, the prostitution is kept

so hidden that it’s almost impossible to figure out what’s going on,”

said Carol Jenkins, coauthor of a World Bank report on HIV and AIDS in the

Middle East and North Africa.

Meanwhile, the general public doesn’t seem to know much

about AIDS or have much interest in learning about it.

“We used to have in our [news]paper that this disease

is not present in our country because we are morally, culturally and

religiously” superior, said Dr. Mervat El Gueneidy, a consultant with

Egypt’s AIDS hotline. “So people would not even try to learn about it

because it’s not our disease, it’s the disease of those bad people.”

An October article in a student newspaper of the American

University in Cairo noted mixed feelings about having HIV education available

on campus. Some said they knew enough already; others thought there was no

such thing as too much information.

And some, like the student union president who called HIV

a “shameful disease,” worried that an awareness campaign would encourage

people to have sex.

In 1996, with the assistance of the Ford Foundation, the

health ministry’s El-Sayed started the AIDS hotline as a way for people to

get information anonymously. In the early days, callers had questions about

basic reproductive biology and sexuality, not just HIV.

The hotline’s El Gueneidy hoped the service would also

discreetly broaden sex education for women, but men make up the overwhelming

majority of callers. Women are more likely to be illiterate, so they may not

be aware of the service, she said. There may be no phone in the home, and they

may be uncomfortable asking sensitive questions on a public phone.

There are still myths that need to be dispelled, such as

the idea that AIDS can be avoided by not having sex with a foreigner—which

does not keep young Egyptian men from trying to strike up conversations with

female tourists, whom they think are more promiscuous than their countrywomen.

Another common belief is that HIV patients are

quarantined, a rumor that is hard to refute because not even foreign and local

health experts are convinced that it’s an urban legend.

“Once you’re found to be HIV positive, the police

show up at your house and accompany you to the fever hospital,” Jenkins

said. “If international donors came and talked to people they would be told

that doesn’t happen. But we know it happens.”

Others say AIDS patients were quarantined in the past,

but it doesn’t happen anymore.

“This is 10 years before,” said Dr. Cherif Soliman,

of Family Health International, the agency that helped develop the new

anonymous HIV testing program. “Now, they can go out and in, they have no

problem.”

El-Sayed, of the health ministry, just laughed at the

quarantine notion.

“Never happened,” he said emphatically. “This

happened in a movie and the people believe the movie was fact. They mentioned

in this movie that any person who had HIV, they put in quarantine. But we

never had a quarantine.”

There is far less stigma attached to AIDS now, El-Sayed

continued. Fifteen years ago, his experience was that family members typically

demanded that their HIV-positive relative be kept in a hospital.

“They didn’t want to take [them],” he said. “Now

almost 97 percent of the families are accepting.”

Could It Explode?

So far, low infection numbers and conservative sexual

behavior seem to have prevented the rapid spread of the virus in Egypt.

How long that will last, though, no one knows.

To get an epidemic rolling, an HIV-positive person “has

to infect more than one person,” said Karen Stanecki, a senior advisor on

demographics for the United Nations AIDS agency.

“People tend to think that once it gets started, it’s

just going to explode,” she said. “But that’s not necessarily the case.

If it’s just a very small group of people then it’s not necessarily going

to break out into any kind of major epidemic.”

But behaviors can change, especially with globalization

increasing the movement of people and ideas across borders, and very little

research is being conducted to keep tabs on the cultural landscape.

For example, even though sex outside marriage is

considered illicit, a study conducted by Family Health International and the

U.S. Agency for International Development found that 16.5 percent of about

1,200 unmarried Egyptian university students have had sex.

And there has been an increase in unofficial “orfi”

marriages, which fulfill people’s desires for a romantic, sexual

relationship in a climate where weddings are extremely expensive. Orfi unions

are not legally binding, so there are no protections for the partners, or

their children, if the relationship sours.

“You have to be ever vigilant as to what’s happening

in terms of changes in behaviors,” Stanecki said.

Public health experts say societies cope best with HIV

and AIDS when leaders talk about it openly. But such discussions can still be

divisive in the Muslim world.

In 2003, American professor and Muslim theologian Amina

Wadud presented a paper at an HIV conference for Muslim scholars in Kuala

Lumpur, Malaysia.

Among other things, she said that Muslim women are more

vulnerable to getting HIV because they’re expected to have sex with their

husbands, who are under no obligation to say whether they are infected with

the disease.

Those remarks infuriated some audience members, 10 of

whom walked out. The moment became a hallmark of the tension between religious

traditionalists and reformers.

Theologian Farid Esack, who cofounded a South African

group to support HIV-positive Muslims, said he believes some people rely too

much on the moral code of Islam to protect them from HIV.

“I think the religious factor is overplayed in the low

prevalence rate in Arab countries,” he said. “Real Muslims are . . .

having sex outside marriage regardless of what the Quran says. And somebody

has to deal with the real consequences of this.”

Even if a rigorous surveillance effort were to confirm a

low prevalence of HIV, “it doesn’t let you off the hook,” said

Hopkins’ Ghanem. “In fact, it should prompt you to be more aggressive from

the prevention standpoint.”

As the experience of other nations has shown, he and

other experts say, it’s never too soon to act.

[Home] [World] [Egypt]